By Sophie Hutchison, Third Year, History of Art

Content warning: this article contains references to eating disorders and their glamorisation, and an image that some readers may find distressing.

The Croft Magazine // TikTok has gained a lot of attention in the past few months, but some users are pointing to its damaging potential. Content glamorising eating disorders goes unregulated, and some fear that young people's exposure to it could put them in danger.

Launched in 2014 as Musical.ly – the lip-synching app which spawned infamous internet stars like Jacob Sartorius – it was only a year or so ago that TikTok gained major traction. Even back then, it was mostly associated with dance videos, but recently it has become much more.

The app has kept many of us, myself included, entertained over lockdown; creators post genuinely good content, from Vine-style comedy videos and videos showing off impressive artworks, to tutorials on everything from sewing to cooking and highly useful videos recommending products you never knew you needed.

That said, TikTok has its issues – from cyberbullying to seemingly unavoidable content that has led to some people experiencing a negative impact on their mental health. Is the app really just harmless fun, or could it be a danger in disguise?

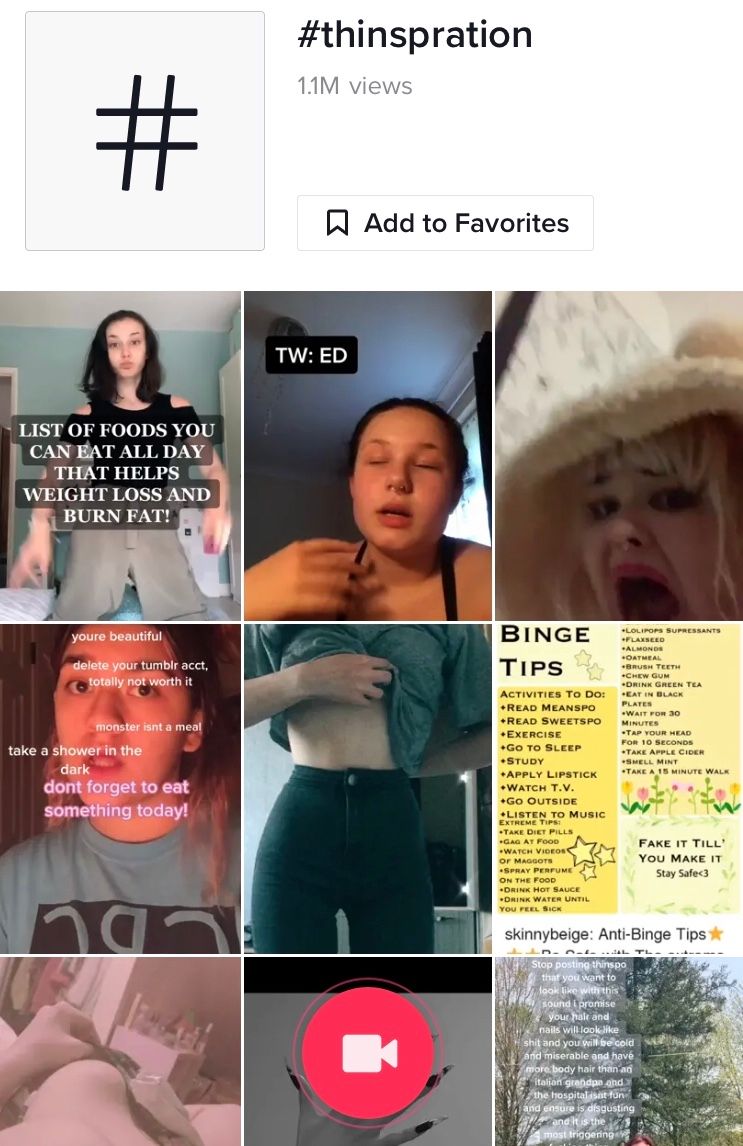

The issue which has perhaps gained the most attention as of late is the prevalence of content on TikTok that glorifies disordered eating. The ‘For You’ page, or FYP, presents users with an infinite string of videos when opening the app – these videos are tailored to the user’s interests, but how TikTok’s algorithm works is something of a mystery.

There is a fairly high chance that young girls will stumble upon content that focuses on eating disorders

It appears, however, that content is gendered – for instance, if a young teenage girl interacts frequently with videos by the likes of Charli D’Amelio, it’s likely she’ll be recommended more content from other young women.

Whilst this more often than not manifests itself innocently enough as videos showing clothes hauls, hair routines, and singing videos, there is a fairly high chance that young girls will stumble upon content that focuses on eating disorders. Some accounts glorify disordered eating and show users’ ‘progress’, documenting the unhealthily low amount of calories consumed that day and showing the resulting weight loss.

These so-called ‘thinspo’ accounts have long plagued social media platforms: first, they took to Tumblr, then Instagram, then Twitter. Pro-ED content is not an issue that is new or exclusive to TikTok. As somebody who spent many hours viewing those accounts as a young teen, I feel that the content that normalises eating disorders is arguably more dangerous.

On TikTok, young girls are exposed to content that makes disordered eating into a joke that all the cool girls seem to be in on

Even as a twelve-year-old it was very obvious to me that, though I wanted to be like the thin girls I saw on Instagram, what they were doing was not normal or healthy. They would post black and white images of emaciated girls and quotes about how ‘nothing tastes as good as skinny feels’, they would caption their photos chastising themselves for eating more than 300 calories; looking at those accounts felt like my dirty little secret – I knew it was wrong.

Yet on TikTok, young girls are exposed to content that makes disordered eating into a joke that all the cool girls seem to be in on. Just the other day, I opened the app and was met with a video of a very pretty girl making a joke about skipping meals and drinking black coffee instead.

Further down my feed was another teenage girl showing a slideshow of her ‘favourite foods’ to background music – those ‘foods’ being diet coke, sugar-free gum and water. ‘Real ones will know’, she’d captioned it as if having an eating disorder is some kind of exclusive clique. One girl commented that she had added the items mentioned to her shopping list.

Whilst the creators of these types of videos argue that TikTok provides them with a platform to share and deal with their trauma, I dread to think what twelve year old me would have thought had she stumbled upon those videos – probably ‘everybody must be doing this; so I should too’.

The platform seems to thrive on toxicity

And it isn’t just the eating disorder content that makes TikTok a potential danger to its users. Whilst trolling is an internet-wide issue, TikTok’s 'For You' page once again makes it easier to fall victim: even the most innocuous video only meant for friends could appear on hundreds of people’s feeds and consequently, could gain unwanted negative attention.

A friend recently posted a video of her playing with her cat and within minutes had received comments calling her abusive – which is untrue and obviously upsetting. Whilst at the age of twenty she was able to brush it off and move on, I fear for younger users who might be more affected by unwanted comments.

The platform seems to thrive on toxicity: ‘duets’ allow users to add their own commentary alongside someone else’s video, which lends itself to mockery that can quickly spiral out of control and become vicious.

The recent trend of ‘fairy comments’ in which users post abusive comments alongside emojis of hearts, flowers, and fairies has gone as far as encouraging suicide. And misogyny, classism, and racism run wild – few and far between are comment sections that do not contain some variation of ‘get back to the kitchen’ or ‘um, actually, ALL lives matter’.

Like Instagram, TikTok shows life mostly through rose-tinted glasses; it puts forth ideals to its users, whether by showing people with perfect bodies dancing on beaches, showing house tours of homes larger than most of us will ever live in, or by showing users a seemingly unending list of things they ‘need’ (clothes, makeup, useless junk from Amazon…).

Yet TikTok is like Instagram on steroids in this regard: whilst on Instagram, it’s possible to curate your feed and unfollow those whose incessant posting of their ‘oh-so-perfect lives’ might harm your mental health, on TikTok, it’s inescapable.

Whilst TikTok has been an easy source of entertainment over the past few months of boredom, perhaps it’s time we put it to bed now. The app has not been without its more redeeming moments: it’s been used to promote Black Lives Matter, organise protests, highlight issues like sexual assault and mental health awareness, and yes, I have bought a ludicrous amount of skincare thanks to TikTok and my skin is absolutely glowing.

All that aside, I worry that TikTok is creating a generation of bigots and I worry about how it’s going to affect the children who are growing up with it. When I take a step back, I realise how it has affected me too.

For information and support with eating disorders, see the following resources:

Beat - The eating disorder charity / Helpline 0808 801 0677 / Studentline 0808 801 0811

Featured image: Unsplash / Kon Karampelas

Find The Croft Magazine inside every copy of Epigram newspaper.