By, Guy Taylor, Second Year, History

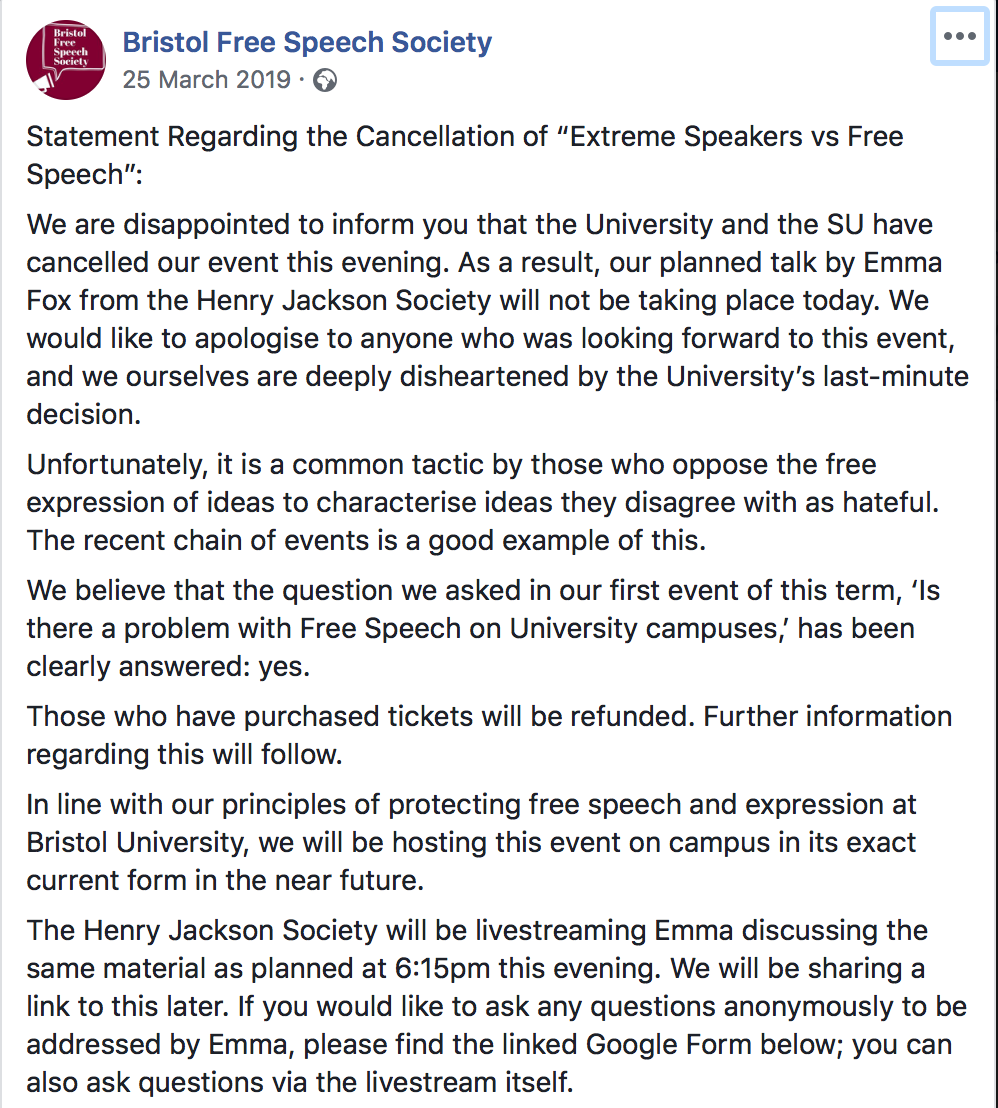

Williamson highlights the expulsion of students for the expression of religious beliefs, for example Felix Ngole who was expelled from the University of Sheffield for sharing comments on social media, which claimed that God identifies homosexuality as a sin. Indeed, examples of hostility and conflict towards those who hold controversial opinions are not hard to come by.

“Anti-Israel students protest UK & Israeli military speakers at Bristol University.” Intent on denying freedom of speech and academic discourse to advance their warped racist agenda, they tried & failed to stop the @PinskerCentre event at Bristol. https://t.co/XMYGmRPk85

— Rɪᴄʜᴀʀᴅ Kᴇᴍᴘ ⋁ (@COLRICHARDKEMP) February 13, 2020

Attempts made to no platform famous activists such as Germaine Greer show that there is a student dominated movement, which believes that offence is solid enough grounds to block an opinion from being expressed. In this respect, Williamson is correct in calling attention to the issue. Subjective offence should not be the measure by which a university decides what should or should not be said.

However, in the case of the free speech debate, there is often a temptation to overstate the extent of the problem. Studies conducted by the BBC found that since 2010, only sixteen universities have received formal complaints about speakers and nine events were cancelled. Freedom of information requests revealed, across 120 universities, there had been no instances of books being removed or banned and only six occasions in which universities ‘cancelled speakers as a result of complaints.’ Broadly, it seems that universities are promoting an environment which facilitates debate and a diverse set of opinions, although that is not to say that this is not under some level of threat.

Taking this into account, the strength of Williamsons argument is not as an alarming call for substantial action to stop a crisis, but rather an early warning that attempts to suppress opinion on the grounds of offence, through the use of threats of violence, should never be tolerated. Government action, in this very specific area, would be welcome. No matter the national scale of the issue, there should be no tolerance for intimidation or threats of physical violence becoming effective tools to no platform speakers.

An excellently written and insightful interview of John @Baird by @EpigramPaper's @robinnlcc on intellectual diversity in higher education, open dialogue, the power of young people in #politics, and the continuing debate over #campus free #speech. https://t.co/tEQPcMLIA7

— The Pinsker Centre (@PinskerCentre) January 30, 2020

Furthermore, at this time, the issue is compounded by the internet and political culture that exists today, where baseless accusations are often thrown around at commentators of all political persuasions. Claims that Peter Tatchell, a leading gay rights campaigner and activist for the past 50 years, was a racist were circulated throughout twitter and other forms of social media, with little to no evidence, and fuelled an attempt to no platform him before a talk at Canterbury Christchurch university. From this example, it is easy to see how a situation could develop in which claims with little basis in reality could be used to prevent discussion on certain topics. Add to that an environment in which threats of violence have the power to prevent subjectively controversial views from being expressed at university, and government intervention becomes an increasingly necessary strategy.

Subjective offence should not be the measure by which a university decides what should or should not be said.

Williamsons suggestions are hardly revolutionary. He suggests a ‘zero tolerance approach to the perpetrators, applying strong sanctions and working with police where appropriate to secure prosecutions.’ Targeting those who threaten others or commit acts of violence would provide a strong defence for all speakers on campuses, allowing for safe, open discourse at universities.

Furthermore, Williamson calls for stronger codes of conduct which recognise that speeches will ‘sometimes cause offence.’ This is incredibly important as it is the idea of offence as an unacceptable evil that underpins much of the no platforming discourse.

If universities could unconditionally accept that it is inevitable and acceptable for opinions to offend, it would go a long way towards resolving this issue. Couple that with government intervention to ensure that a zero-tolerance policy towards threats of violence is adopted and talks from the likes of Greer and Tatchell would no longer be under threat.

Do you think there is a problem with free speech on campus?