By Polly Ovenden, Fourth Year, Law

CW: This article contains detailed discussion of eating disorders, specifically Anorexia.

For Eating Disorder Awareness Week, Polly Ovenden recounts her experience after being admitted to an Anorexia recovery centre as a day patient.

After dropping out of University right before my final term of my Law Degree, everything was a blur. At the stage I was at, I was told a hospital admission was likely. Luckily, I was put on a waiting list for a NHS Day-Patient recovery centre, which was on the edge of my GP catchment area, despite being an hours drive away. I would have to attend five days a week, 8.30am – 5.00pm, for an indefinite period of time. I was there nine months, but the tough regime and institutional approach meant I saw over twenty-five people drop out before they could get any better.

Anorexia is a mental illness with severe physical symptoms. It has the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. If you do not know anything about it, I can only describe it as having a voice in head, constantly screaming at you; wearing down your self-worth and instructing you that you are ‘not good enough’ for food. For me, I was begging to be helped. I was caught in a toxic cycle, and it felt like there was no way out – I had lost control. Being admitted to Farnham Hospital saved my life, but everyday was a battle to get up, show up, and find the courage to fight my illness.

While the NHS system is far from perfect, and treatment felt unbearable, I knew that the only way out was to trust the professionals and battle through.

While I was lucky, and thankful to be admitted to this programme, I am sure it will be the hardest nine months of my life. In the midst of an Eating Disorder, food is terrifying. While it may seem so simple on the outside – that you just need to eat more food, when you are in that dark place it feels impossible. The two worst things at Farnham were being weighed and the food.

Your treatment at the Hospital was dictated by your weight. You were weighed twice a week, and this was plotted on a graph. I hated seeing, what felt like my existence, represented as a number; one line plotted weekly on a graph, dictating my future and how ‘well’ I was doing.

How can we improve the lives of people with Eating Disorder? https://t.co/pOjfjCbYct #EatingDisorders2019 @hcuk_clare pic.twitter.com/y8gzqj6gvY

— Beat (@beatED) February 17, 2019

NHS funding for eating disorders is scarce. Funding constraints mean the NHS has to find a way to delegate on a basis of need. Unfortunately, the current system directly correlates the severity of a BMI to available treatment. This should not be the case; early intervention would prevent many sufferers deteriorating to the point where an admission is necessary.

However, everything at Farnham was related to a BMI. At ‘X’ BMI you were allowed to progress to Stage 2 of treatment, ‘Y’ BMI meant you were allowed Wednesday afternoons off. If you lost ‘Z’ kg you would be kicked out of treatment. While it is imperative that mental illnesses are treated holistically, limited resources have led to a system based on numbers.

The food was the same as the other patients in the hospital. Mealtimes were tense; we all sat in a windowless dining room, the atmosphere tense, with a falsely cheery radio soundtrack in the background. Two eating disorder nurses sat and ate with us, and they would prompt us to finish everything.

Because you were together all day everyday, exploring every innermost thought and feeling, you became very close, and found motivation in others progress.

To treat Anorexia you need to address the physical and mental symptoms. At Farnham we had weekly psychotherapy, C.B.T, and D.B.T sessions. They targeted different areas of the illness to encourage us to start challenging the negative and compulsive though patterns, and learn about what contributed to the illness manifesting.

This was a group programme; so all therapy sessions were with the other patients. This was sometimes hard, because as well as battling your own eating disorder, you were exposed to everyone else’s journey whilst they dealt with grief, abuse, abandonment and depression. Because you were together all day everyday, exploring every innermost thought and feeling, you became very close, and found motivation in others progress. But being this close could sometimes be detrimental, with constant ‘triggers’ all around and toxic negativity creating a stifling atmosphere. It was another challenge, to dig deep and the find the motivation to choose Recovery.

I saw many people come and go when I was at Farnham. If I had not had the support of my family, I do not think that I would have gotten through it. While the NHS system is far from perfect, and treatment felt unbearable, I knew that the only way out was to trust the professionals and battle through; otherwise the illness would hold me captive for eternity. I was lucky to have the right treatment when I was ready to accept it. The NHS system is far from perfect, but for me, thankfully, it worked.

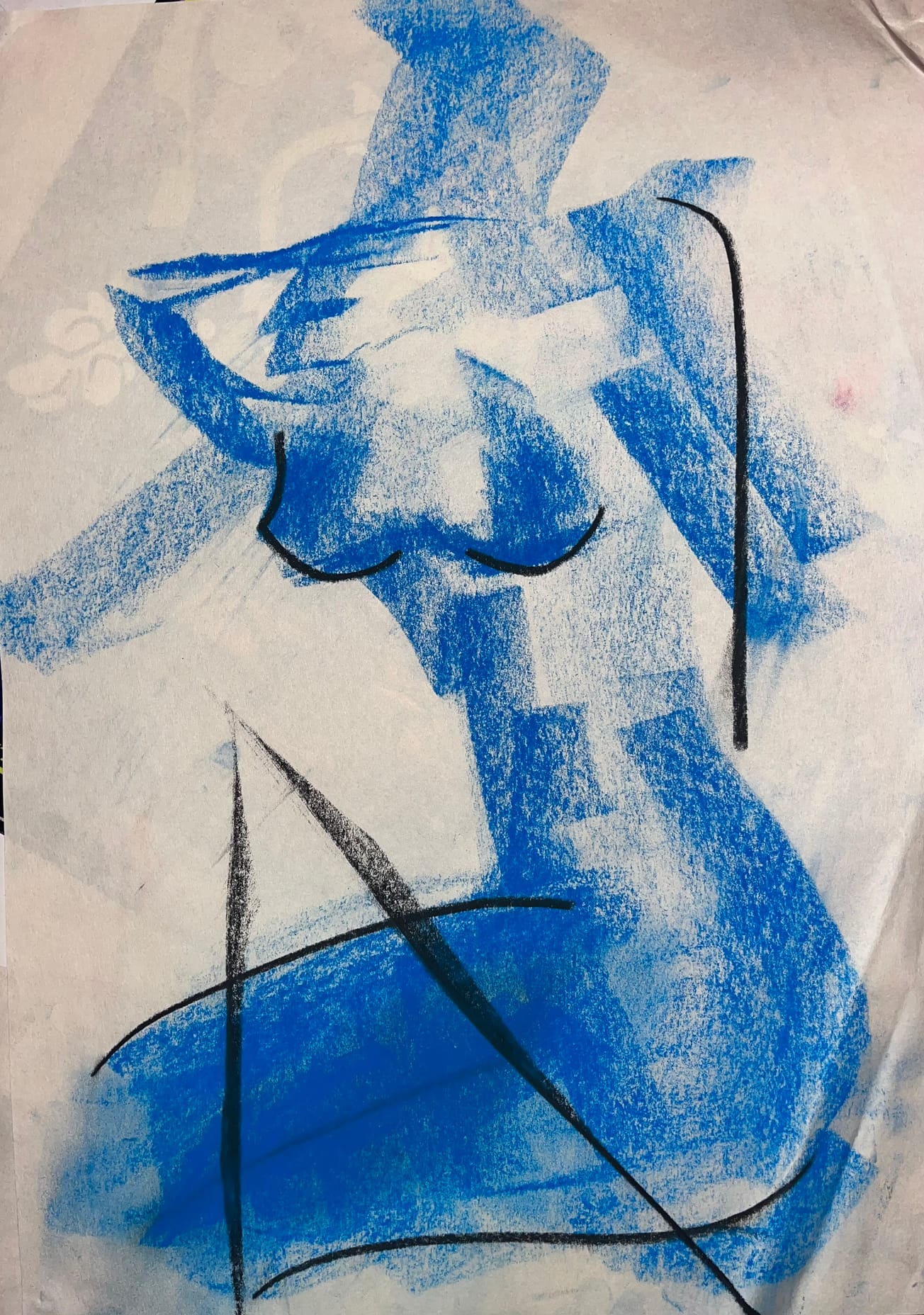

Featured Image: Epigram / Polly Ovenden

If you feel that you could benefit from help regarding any issues related to this article, contact the student health service, or ring the Beat student line at 0808 081 0811.