Sophie Shanahan, First Year Law and German

It is increasingly known that social media has a growing impact on one's mental health. In a society which is focused on how we look and present ourselves, Sophie talks about the negative implications of being so invested in our image and the image of others.

I took the decision a few months ago to unfollow every account on social media, particularly Instagram, that made me think badly of myself or my life. At the time, this was mainly to cut back on the endless hours I could spend online, and in turn, hopefully to benefit my wellbeing. Since then, I have replaced some of these accounts with those of ‘influencers’ who provide more honest representations of themselves, and, through these, have become more interested in the extent to which the accounts I followed before would doctor their images. I realised that I hadn’t even considered that these beautiful people I saw everyday may not have been as perfect as they had seemed, and began to wonder whether my self-deprecation was rooted in something that wasn’t even real.

The editing of images in the media was once limited to the pages of glossy magazines, and it got to a point where photos of models and celebrities began to be doctored to such a ridiculous extent that we began to distrust them. This then led to widespread campaigns against the routine airbrushing of images, and there has since been a significant reduction in the level of ‘photoshopping’ employed in the mainstream media. This is not to say the problem has reduced as a whole, however. In fact, I would argue that the prevalence of social media has been a major enabler for this practice. The editing of images on social media can range from the healing of spots, to the bleaching of skin and pumping of muscles. These techniques may seem small and inconsequential to those who employ them, but when our internet scrollings constantly bring up images of ‘perfect’ faces and bodies, we’re bound to start believing this is how we should also look.

We have to outlaw airbrushing in the US/UK. I always fight for no editing. It makes me feel bad about myself when an editor decides that my cellulite, stretch marks or squishy arms/thighs or ethnic nose were too shameful to be seen in public. It's all a part of me, and I like it.

— Jameela Jamil (@jameelajamil) April 11, 2018

At the point I decided to purge my following list, I was beginning to realise that each account I was following was staring to blend into one, with each person trying to smooth themselves into some kind of beige, boring mould.

When our internet scrollings constantly bring up images of 'perfect' faces and bodies, we're bound to start believing this is how we should also look.

Jameela Jamil has been one of the loudest online voices in the campaign against altered images being posted on popular Instagram accounts. When I first came across her, I really started to get interested in the subject. As a former model, Jamil had first-hand experience of the pressures to airbrush images and had later committed to never allowing her images to be edited in this way. Although Jamil herself is conventionally beautiful, she is not unattainably so - the images of her own dark circles and stretch marks showcase her humanity in a healthy way that I admire much more than the plastic faces that once littered my feed.

The power of people in my position not editing things like stretch marks (as seen on my boobs), is that, thousands of people realize they are not freaks for having the same thing. I got THOUSANDS of msgs thanking me for posting this because it made them feel better and normal.❤️ pic.twitter.com/OL9ZRjJM7v

— Jameela Jamil (@jameelajamil) December 4, 2018

What I view as the primary danger of these accounts is how they create a new ideal towards which their followers start to want to strive. Even more dangerous is how this standard not only seems out of reach, but actually is completely unattainable. We are under no obligation to disclose whether our photos are edited, and so it is likely that many consumers are completely unaware that the images they are seeing are false. These accounts are presenting unreal realities: creating faces and lives that do not exist. Reaching for a goal that can never be realised can only lead to frustration and disappointment, and the consequences of this can be unimaginable. Countless sufferers of body dysmorphia and eating disorders attribute, at least in part, the onset of these conditions to social media, and the pressures they felt from the impossible standards showcased on their screens.

Even more dangerous is how this standard not only seems out of reach, but actually is completely unattainable.

A second danger is how the editing of photos for social media is slowly becoming the norm. With in-built editing software on all mainstream photo-sharing platforms, as well as easy access to more advanced apps and computer programs, hardly a single photo appears on my screen that hasn’t been altered in some way. Even Instagram filters that seem harmless may hide spots or cellulite and shield us from accurate representations of our friends’ lives. I try not to edit any photos with people in anymore, as I found I got to the point where I couldn’t upload a photo of myself unless I felt I looked completely perfect. This led to me hardly ever sharing on social media and meant that I had to admit that I was not only never going to look like the influencers I so wanted to, but also that even the images I uploaded of myself were unattainable.

Realising I was becoming part of the problem really shook myself out of the false world I had become so tied up in, and led me to actually enjoy sharing photos that truly reflected my life. I now get so frustrated when I see clearly doctored images still popping up in the media, and have learned to pay more attention to those who embrace themselves as they truthfully are - humanity is much more interesting in its honest form.

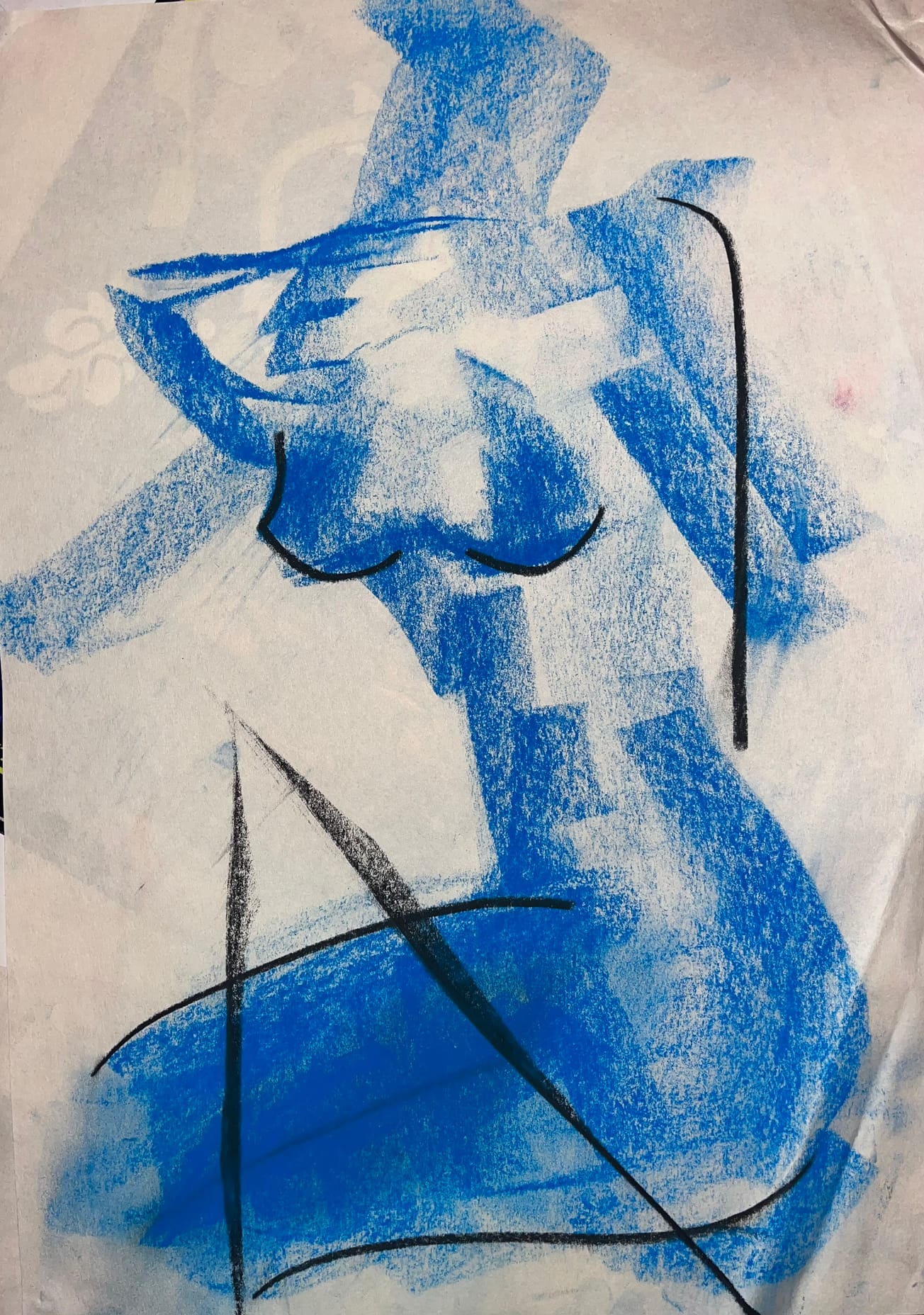

Featured Image: Unsplash / Le Buzz

Are we entering a world where we edit ourselves to a worrying standard? Comment below or get in touch!