By Hope Riley, Living Editor

At university, we are always being exposed to new people and new ideas, and as a result one’s identity and sense of self is in a constant state of flux. Particularly when taking into account the overwhelming presence and invasive nature of social media, it is easy to get bogged down with the anxiety of how you are presenting yourself to others, and to become overly concerned with the minute socio-centric details of the quotidian. However, rather than clinging to notions of ‘the self’ – and worrying about how you are being perceived – it is important to find time to zoom out, and remind yourself of what it is that gets you out of bed in the morning.

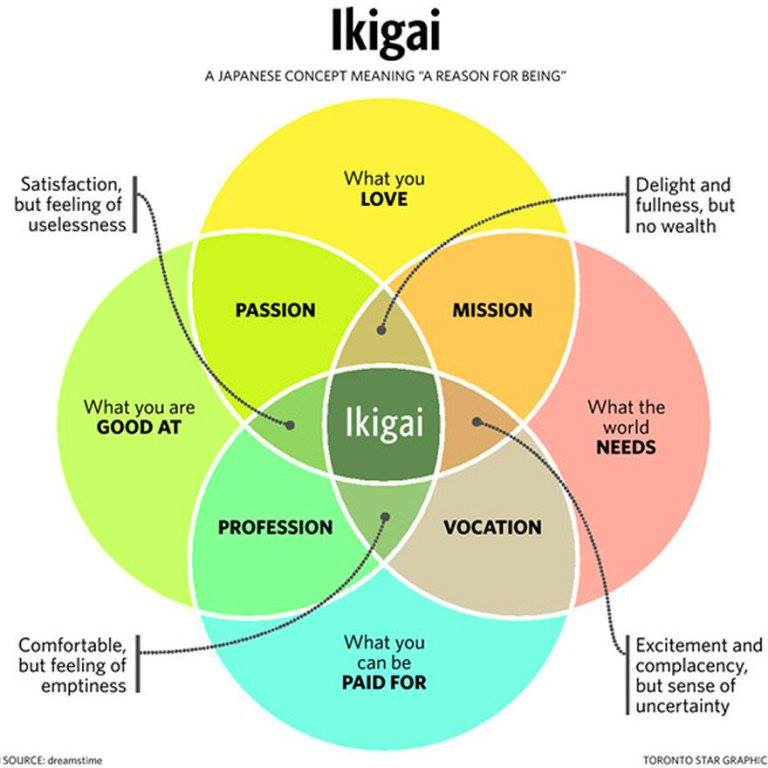

I recently did some research into the Japanese lifestyle concept of ikigai, which can be roughly translated as ‘a reason for being.’ This self-development philosophy dates back to the Heian period (794 to 1185 A.D.), and is rooted in the idea of living in happiness.

With its origins in the Japanese island of Okinawa, ikigai is described by American lifestyle columnist Thomas Oppong as ‘the secret to a long and happy life.’ Indeed, Okinawa itself is home to the greatest proportion of centenarians (persons over a hundred years of age) in the entire world, with 740 in a population of 1.3 million (Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2006).

Whether there is any truth in the concept of ‘mind over matter,’ or in the idea that a healthy mind equals physical health or longevity of life, the Okinawans certainly seem to be doing something right. So, according to my research, the secret to discovering your ultimate ‘sense of purpose’ is all about balance – finding the perfect equilibrium between the four essential pillars of ikigai:

- What (or who) do I love?

- What am I good at?

- What can I do to earn money/ a decent living?

- And finally – what does the world need? What can I give back?

@rebecca_bakken / Instagram

While the answers to these four questions form the basic foundations of ikigai, this does not mean you must adopt a reductive approach to living – I think it is entirely possible to apply the concept of ikigai to your lifestyle as a liberal, forward-thinking Bristol student. Indeed, in its origins, ikigai was a heavily gendered concept – a woman’s ikigai lay traditionally in her family and the domestic sphere. And – you guessed it – a man’s was in his commitment to work and his role as breadwinner. The ikigai philosophy is in a process of evolution, however, and has survived ancient Japanese social hierarchies to be adapted to the lives of many modern thinkers across the globe.

Challenges are opportunities for me to grow. The more I learn, the more equipped I am to handle whatever situations come up. #qoute #quoteoftheday #Friday #challenge #BlessedFriday #ikigaiJordan #ikigai #selfawareness #purpose #Birkman #Counseling #thebirkmanmethod #Amman #Jo pic.twitter.com/sTFTGV91o4

— IKIGAI JORDAN (@IkigaiJordan) October 12, 2018

According to Toshimitsu Sowa, C.E.O. of HR consulting firm Jinzai Kenkyusho, ‘Japanese workers are driven by being useful to others, being thanked, and being esteemed by others.’ When applied to university life, remembering your ikigai can make sitting through a boring lecture feel less pointless, when you consider that through study you are working towards tangible career objectives. By going to the gym or cleaning your kitchen you are proving that you are committed and good at self-discipline. By spending time volunteering or donating money to charity, you are being pro-active and conscious of what the world is missing.

reflect on the people in your life that bring you joy and happiness

Following your ikigai awards you total autonomy over whatever it is you choose to pursue as a hobby – or even career – since the end goal always lies in achieving an entirely personal level of happiness and fulfilment. It also promotes less of an individualistic outlook on life, since you are encouraged to relate your actions more broadly back to the world and what it is ‘in need of.’ In his book The Stuff of Dreams, Fading: Ikigai and ‘The Japanese Self,’ Gordon Mathews points out the differing notions of Japanese selfhood when compared to Western ones. He notes that Esyun Hamaguchi (1985) ‘labels the Japanese self kanjin, meaning “the contextual,” as opposed to the Western kojin, the individual.’ In this way, Japanese followers of ikigai are more community-focused than what Mathews perceives as the more self-orientated ethics of Westerners.

My intention in writing this article is not to throw you into a premature existential crisis over pin-pointing that specific aspect of your life that can be defined as your ‘ikigai.’ Instead, I encourage you to reflect on the people in your life that bring you joy and happiness, on those memorable experiences that have shaped who you are as a person, and on the hard work and commitment that has got you to where you are as a student of Higher Education today.

Featured image: Evgeny Lazarenko / unsplash

What do you think about the philosophy of ikigai? Can you identify yours? Epigram wants to know! Get in touch!